Pagliacci meets the heist genre in a comical crime caper that proves there are no easy getaways.

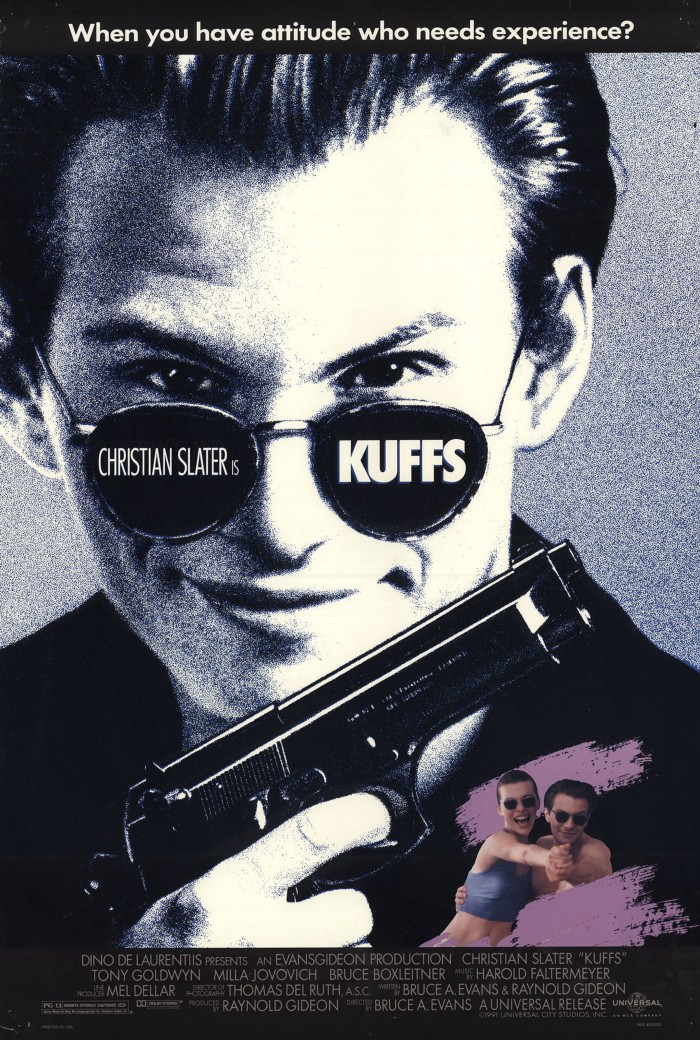

In July of last year I initated a review of the late ‘80s/early ’90s sub-genre I’ve dubbed the “cromedy” (crime/comedy), beginning with early 1992’s Christian Slater-starring Kuffs as my inaugural piece. This article will constitute the second in what I’d like to make an ongoing series.

But why bother commencing a cromedy concatenation, especially about a largely underappreciated sub-genre relegated to a bygone era? There are several reasons. First, a personal one. Many of these films were in perpetual rotation on such channels as TBS Superstation and USA back in the late ’90s, a time when I was a teenager and constantly curating my isolative boredom on the weekends with middling minor hits. The network channels had all the big movies (which I’d already seen), and my house didn’t have premium cable. So, I satisfied myself with more niche fare. Most importantly, this was a sub-genre I’d discovered for myself, rather than one presented or pre-screened for me by friends, family, or parents.

Secondly, I’ve recently begun seeing movies beyond mere vehicles of entertainment, but as time capsules. Little glowing glimpses to particular periods in history. The crime/comedy sub-genre is, of course, not unique to the late ‘80s/early ’90s. Abbott and Costello were satisfying studio contracts with such films as Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man and Meet the Killer, Boris Karloff back in the 1940s and ’50s. However, the “cromedy” era is one I’ve designated as ranging from about 1984, with the release of Beverly Hills Cop, the sub-genre’s undisputed apex predator, concluding with the Tarantino-penned True Romance (1993). The foot fetish dialogue virtuoso would effectively obliterate cromedies forever with Pulp Fiction the following year, a film that instantly rendered any crime flick obsolete if it didn’t have henchmen riffing on about cheeseburgers and pop culture.

Odd as it is to say, but American movies set in the late ’80s/early ’90s, and earlier, are practically period pieces at this point. They depict a very different cultural landscape. Before the internet, cell phones, social media, largescale racial integration, and the financialization and digitization of the economy. Politically, the era takes place right at the tail end of the Cold War, and well before 9/11 pricked the USA’s bubble of security. People smoked (on airplanes even!) without verbal warning signifiers, words like “faggot” and “retard” were casually slung around by film protagonists, and sexual harassment and violence, even against underage teens, were often playfully portrayed. Unacceptably strange behaviors that would obviously never fly in today’s Puritanical woke climate.

Aside from Eddie Murphy’s monster ’84 smash about a Detroit cop who fish-out-of-waters in upscale L.A., and A Fish Called Wanda, there are few if any other diamonds in the cromedy genre. It’s an oddball assortment of sapphires, rubies, occasional pearls, and a whole lot of quartz.

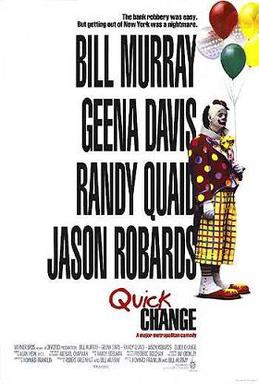

Which brings me finally to Quick Change, a strong sapphiric entry. A 1990 crime comedy starring Bill Murray, Geena Davis, and Randy Quaid as three bank robbers who pull off the perfect heist on a New York City financial institution, only to get hilariously bogged down in Looney Tunes-esque fashion in their escape from Gotham. The film remains Murray’s only directing credit, a distinction he shares with Howard Franklin, who co-helmed the picture.

Despite having watched the film numerous times during its syndication heyday on cable in the late ’90s, and then again recently, I only just find out that it’s actually based on a book. The novel of the same name was published in 1981 by Jay Cronley. Cronley was an author of eight comedy novels, most of which became films in the mid-80s through 1990, starring such actors as Chevy Chase (Funny Farm) and Richard Dreyfuss (Let It Ride, based on the novel Good Vibes).

If the cromedy genre has Founding Fathers, Jay Cronley is perhaps its Ben Franklin. Even his last name sounds serendipitously similar. Cromedy/Cronley. How nice is that?

According to Cronley in his introduction to the 2006 re-release of his novel Quick Change, he spent almost a year wracking his brain looking for the last great heist idea. His efforts more than pay off with a clever high-concept robbery that appears to do a little more than inspire the Joker’s mob bank hit in the opening to The Dark Knight 18 years later. Granted the Joker character predates Quick Change by decades, and the Clown Prince of Crime no doubt pilfered many a vault in the comics, but I’d be surprised if Christopher Nolan hadn’t seen and been a fan of the Bill Murray film before making the Batman sequel.

Murray, playing “Grimm,” shows up a Manhattan bank dressed in a full-on clown costume, complete with a suicide vest packed with dynamite. After initially failing to garner any attention with his droll announcement that “this a robbery,” (this is Manhattan, afterall) he fires his gun into the air. That does the trick. Police are summoned by the notorious under the counter RED BUTTON alert system, and a SWAT team assembled. The criminal clown is quickly surrounded. Except this is all part of his perfect plan. Grimm makes some outrageous demands, including a monster truck, which the hapless but earnest Police Chief Rotzinger accommodates in exchange for hostages. Except the first three hostages are actually Grimm’s accomplices, Phyllis (Geena Davis) his girlfriend, Loomis (Randy Quaid) his childhood best friend, and Grimm himself (sans clown make-up). Who have all taped the stolen money under their clothes. Hence the film’s double-meaning title.

Unrecognized due to disguises, the trio slip away to a rendezvous point in a ghetto section of town, where they plan to leave for JFK Airport and eventually, a spot in the Caribbean, with their ill-gotten gains.

It’s a masterful plan. The police are completely fooled. But just when it appears Grimm and company are set to make a clean getaway, all their good luck runs out. They get lost en route to the “BQE” (Brooklyn Queens Expressway), held-up by a gun-wielding apartment visitor, robbed by a conman, lose their car, stymied by a rulemeister bus driver, and have to fool their way through the mob, a foreign cab driver who doesn’t speak English, and a bizarre assortment of NYC characters. All the while Loomis regresses into infantile buffoonery, and just-pregnant Phyllis threatens to leave her beau to protect their baby from a life of crime.

Quick Change has a lot going for it aside from its clever concept. It has some cool cameos, including Phil Hartman, Stanley Tucci, Tony Shalhoub, and a post-Robocop pre-That 70’s Show Kurtwood Smith. An amusing, if one-note, musical score. And some endearingly nostalgic technical touches: Payphones, paper maps, and film spool recording equipment.

The film seems comfortable relying mostly on its comedic sequences. What little dramatic character moments there are barely register. Unlike the turbulently jocular relationship dynamic between Wanda, Archie, and Otto in the smartly-scripted A Fish Called Wanda, another heist film that focuses on the aftermath of the crime rather than the crime itself, Quick Change remains more plot-focused and surface-level. Yet its superficial trappings don’t seem to hurt it. It still boasts witty dialogue, colorful performances, surprising enough twists and turns, all delivered with a well-paced flair. It gets the job done, and more than earns its distinction as a sadly forgotten cromedy gem.

What questionable points remain are largely ignorable, if not workably humorous. Grimm’s bank robbery adds up to a whopping one million dollar haul, split three ways. 1990’s $333,000 in today’s inflation-spiked currency is about three quarters of a million dollars. Hardly enough to go on the lam permanently from law enforcement. Much less raise a new family. Though it comes close to Walter White’s initial, uh, fundraising goal of $737,000, which the chemistry teacher sets for himself when he first starts selling meth in Breaking Bad.

Then there’s the glaring issue of Police Chief Rotzinger seemingly figuring out the criminal trio are escaping on a plane just taking off, after Grimm provides the false name of “Skipowski” (he’d used the name “Skip” as an alias while robbing the bank). Are we to assume the NYC Police Chief wouldn’t have the ability to have a plane grounded if he suspected there were three bank robbers on board, which the city has been on a manhunt for all day? Even as a credulous teen, I found the movie’s ending rather implausible. As a middle-aged adult, even more so. I imagine a Spongebob-style “Three Hours Later” time card popping up, then cutting to Grimm and friends getting arrested on the tarmac by the feds. Fade to black.

For a very brief time, Quick Change was my favorite film, if only because I hardly encountered people that knew it existed and it therefore felt like something I alone had “discovered.” And this was even back in the late ’90s, well before Bill Murray’s resurgence as a serious actor in Lost in Translation and a fixture in Wes Anderson films. As a Murray vehicle, Quick Change’s Grimm hardly competes against his more popular roles. Which is a shame, because it’s one of his most natural performances. Although, I will say that in addition to possibly influencing The Dark Knight’s bank robbery opening, I noticed a lot of similarity between Murray’s quippy, quick-thinking, and smart-mouthed portrayal of Grimm, and Bob Odenkirk’s wily criminal lawyer Saul Goodman. Grimm dances out of danger with his mouth at multiple points. Even talking down a gun-wielding psycho, outwitting a local mob boss, and of course, playfully taunting the police. Grimm and Goodman could practically be brothers.

Quick Change may lack the charisma and energy of Bevery Hills Cop, and the intelligence of A Fish Called Wanda, but as a cromedy entry, it’s a solid sapphire.

Do yourself a favor, and check out Quick Change, both the movie and the book.