So, I was doing some preliminary research on my next film review for the ‘90s-era “cromedy” (crime-comedy) Quick Change, when I stumbled across one of the most hilarious book introductions I’ve ever read.

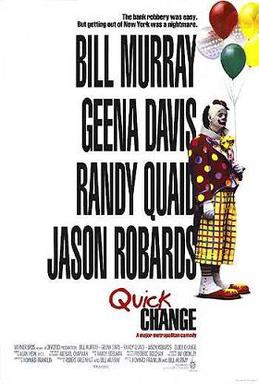

Firstly, since you may not know, Jay Cronley was an author and newspaper columnist who wrote for Tulsa World, who achieved some notoriety in the late 1980s/early ‘90s for a string of comedy films made from his books. These adaptations include Good Vibes, made into the 1989 comedy Let It Ride, starring Richard Dreyfuss. Funny Farm, made in 1988, starring Chevy Chase. And Quick Change, which was adapted twice into film. First in France in 1985, then in America in 1990, starring and directed by Bill Murray, and co-starring Geena Davis and Randy Quaid.

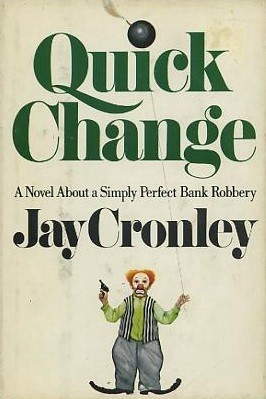

Cronley had quite an under-the-radar run. For awhile, he was like the comedy version of Ira Levin. Everything he wrote got filmed. However, we’re not here to talk about his films, but about his writing. More specifically, his introduction to his 1981 novel Quick Change, rereleased in 2006 (not an affiliate link) with his reflections on the impact of his book.

Quick Change is “about a bank robbery,” as Cronley writes in the opening line of his introduction. It’s a comedy about three thieves who mastermind a clever heist in New York City, only to run into every problem imaginable trying to escape Gotham.

Cronley’s book introduction for Quick Change contains a lot of interesting, useful, and funny writing tips that I felt would be good to share. As an author of dark comedies and satires myself, I certainly appreciated happening across this gem. And I’m someone who almost always skips author intros.

So, here are four writing secrets from Jay Cronley’s Quick Change intro:

1. Dig Deep to Find an Original Idea

Writes Cronley:

Before I began to write this novel, I sat down with a pencil and a notepad and I thought of every way I had ever seen anything stolen…Name it, I noted it. Then I began making notes of all the angles and methods ever used to take what isn’t yours.

It’s fair to say that the crime genre is a fairly well-mined one. Especially with famous authors like Donald E. Westlake (more on him later), Agatha Christie, and classic writers like Edgar Allen Poe and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, among many others, having hatched almost every conceivable crime story over the last 150 years of publishing history. It’s true now. It was also true back in the early ’80s, when Cronley wrote his book.

This sounds like an easy thing to do. Just research a bunch of plots and then write something that hasn’t been done before. What’s so hard about that, right? Except few writers do that. Instead, they grab hold of whatever new idea they have, refusing to let go. But if you’re trying to break through, you have to do something that hasn’t been done before, that will get you noticed ahead of the many other writers working in your genre.

Speaking of genre, this little tip also means you have to know your genre through and through. And that means reading the hell out of it. Or at least knowing some of the common tropes and twists, so that you can surprise with some of your own.

2. Don’t Give Your Good Ideas Away to Other Authors!

Apparently, all of Cronley’s research for the “last great bank robbery idea on earth” attracted the attention of Donald E. Westlake, whom Cronley considered, “arguably the greatest living American writer.” Westlake actually wanted to use Cronley’s idea for Quick Change in one of his own books. But, as Cronley writes:

“No,” I said to Don on the phone that night. “You can’t have my idea. It took me a year to think of it and a year to write it.”

It’s actually rather hilarious to me the idea of Westlake, the legendary crime author with almost 100 titles to his credit, coming to a lesser known author like Cronley hoping to procure a good story idea. It makes me wonder if this is a common thing amongst best-selling authors. It just seems wrong and impolite. Popular musicians borrow, steal, and pay homage to one another all the time, though, so I suppose published authors would do the same. I know I’ve provided good feedback, and even suggested story plots and ideas to other writers on forums and comment threads. But I’ve never given away, or even discussed an idea of mine that I felt had merit for a good book or screenplay.

3. Hollywood Sucks Because Nobody Reads

This is right in line with Stephen King’s famous On Writing maxim: “Read a lot, write a lot.” Cronley, who was criticising the creative shortcomings that were plaguing Hollywood even back in the early 2000s, goes on to say:

The simple reason behind the creative crisis is that nobody reads good stuff, which is the old stuff. The only way to learn how to write well is to read. If nobody reads, you get that Adam Sandler baby-talk thing.

This is especially true nowadays. It is so so easy to get wrapped up in the mindless bits and pieces of Twitter and other short-form-style social media. I find myself getting caught in this no-reading trap all the time. But sadly, so many today are smartphone slaves, addicted to the dopamine-giving hits from divisive news headlines, celebrity gossip, or vapid Buzzfeed-style articles that convey little to no useful information. To say nothing of the infinite scroll of YouTube videos, TikTok shorts, streaming shows and movies, Twitch broadcasts, and immersive video games. Who has time for classic literature?

This problem extends even beyond the general population, to English majors, writers, and novelists like myself, as well. When I was in college, I rarely encountered classmates who’d read much of anything beyond the Harry Potter series, or other modern books published prior to the 1980s. And that’s honestly a crime, because classics are classics for a reason.

4. Movie Deals Don’t Always Lead to a Pot of Gold — In Fact, They Might Even Get You Sued For $10 Million

Quick Change quickly landed a movie option, which is a contract during which someone has a given amont of time to make a piece of intellectual property into a film. Sometimes options may only last for a year, and an author might be paid a few thousand dollars. The company that first landed the option to Quick Change wound up in bankruptcy. Right before the option expired, Cronley’s agent offered the book to a producer in France. However, this caused the first option holder to sue Cronley for almost $10 million.

Fortunately, the lawsuit was eventually tossed. The French producer went on to make Quick Change into the film Hold-Up in 1985, starring Jean-Paul Belmondo. The Bill Murray version would, of course, come later. But it goes to show that sometimes Hollywood deals can actually be spring-loaded boxing gloves ready to punch you in the face.

If you haven’t checked out some of Jay Cronley’s books, now’s a good time. If you can find them, of course. Many of them are out of print. But evidently, judging by the Amazon link above, Quick Change is still readily available.